For the vast majority of young heterosexual men who set off in search of a career in photography (or at least for those of us who are honest about our ridiculous self-delusions) its siren song is often the real or metaphorical promise of “fast cars and naked women”. In the absence of more high-brow and imaginative motivators, I’m thinking “Blowup” and “Austin Powers” here, but for those of you otherly gendered or oriented, please don’t get mad at me, just insert your own intrigues in place of ours. Of course, there are those, like my friend and CDIA colleague Tim Lynch, who got into photography because they were told there would be “no math and no English”, but let’s leave that discussion for another time. The point is, many of us who stick with the business long enough eventually come to realize that, if we’re lucky, the reality of a job as a professional photographer usually amounts to something more like a beat-up Jetta and a loving girlfriend. But there is that rare breed, the ones who make it all the way to the top, who get the cars, the women, the South of France, the Tribeca studios, the monographs, the expensive limited edition of their favorite camera with their name engraved on the top, all of it. They drive the rest of us absolutely nuts, because, as we all like to imagine, we could have, we SHOULD have been them, and if we keep on pushing, we might still be. In other words, we’re jealous.

So, before we start, I should put a few things on the table. I’m a nobody in the world of photography, but I have a high opinion about what it means to be a somebody. The following thoughts should be evaluated based on that understanding. Also, if you’ve read some of the older posts on this blog, you know that I have a Leica rangefinder camera, an M6 that I bought it in 1997 because I wanted to make pictures like Robert Frank and Henri Cartier-Bresson. I believed the hype then, and I still do. Nothing I have learned by using the little device has changed my mind about it. The camera is nearly perfect, and in the hands of someone who knows what he or she is doing, it can elevate that photographer’s process and product— it certainly did mine. But shooting with film cameras, even those as intoxicating as Leica rangefinders, has become less and less desirable as digital tools and technologies have matured. I now strive to make equally sensitive, insightful “old-school” photographs with digital equipment. Nevertheless, as anyone who knows me can certainly attest, I have spent the better part of 30 years sharing my awe and enthusiasm for the medium’s classic stylists and innovators who used the Leica camera. One of them, the heavy-hitter and Leica spokes-shooter Ralph Gibson, spoke recently at Boston University’s Photographic Resource Center.

Tim and I brought our “Photographic Seeing” classes to the PRC that evening for what would prove to be a rich learning experience, although some of us felt that the lessons learned had less to do with creative secrets revealed by a master of the medium and more to do with artspeak, intransigence, and a healthy dollop of good old fashioned ego. Our students seemed to agree afterwards that while art can be transcendent, artists can be somewhat otherwise, and it’s usually a good idea to remember to separate the two. I figured this out a long time ago, but still, by the end of the evening I had begun to ask myself whether everything I believe to be valuable and true about the nature of the type of photography that I love might be suspect. Could it all, to put it delicately, be bullshit?

Thankfully, after about 30 seconds of intense soul-searching, most of my heroes remain firmly plopped high on their pedestals, although my confidence is shaken. Frank, Cartier-Bresson, Lee Friedlander and all the rest are still up there in my opinion, maybe because they mostly managed to keep their mouths shut and let their pictures do the talking. These photographers, in other words, stayed out of the way of their photographs. Or maybe it’s because I just never sat in a room listening to them talk about their own work.

But there we all were with Ralph Gibson. He’s got a lot to say about what he’s done, much of it interesting, some of it supercilious, and a bit of it disappointing. He kicked off his lecture by describing himself early in life as a classic screw-up, a child of a Hollywood divorce and a high school dropout given the choice at 16 of either “the Navy or military school”. Choosing the former, he proceeded to flunk out of the Navy’s photography training program. A second chance at the course (granted only after promising to clean the latrine for six weeks) led to a defining moment: standing watch on deck late one night, he screamed to the heavens “I WANT TO BE A PHOTOGRAPHER!!!” and judging from a career spanning nearly the next half-century, the heavens apparently answered back “well, OK…” Sensing a bit of a kindred spirit, I smiled as echoes of my own early frustrations driving a subway train on endless graveyard shifts while dreaming of a life behind a camera rang in my head.

After his discharge, he attended art school in San Francisco, made the pilgrimage to New York, assisted Robert Frank and Dorothea Lange, and lived the life of a struggling young artist “nine months behind on the rent”. Then, seemingly like magic, he received a commission to photograph “in Fronce”, joined and then left Magnum, started his own publishing company, Lustrum Press, and basically never looked back. Why and how all that so suddenly materialized he didn’t say, but the old adage “if you want to make a million dollars in photography, start with two million” popped into my head as a possible explanation. He had hooked me with the fist-shaking swabby story and reeled me in with imagined coffee-and-donut runs for Frank and Lange, but I started to wiggle off the hook when it all began to sound vaguely pompous and disingenuous, supported by a slideshow that was at best uneven, and at worst, unexpectedly pedestrian.

None of this is meant to suggest that Gibson hasn’t worked hard and accomplished much. Guggenheim fellowships, NEA grants, Leica Medals of Excellence and Officiers de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres bestowed by the French government are not given out to just anybody, and he has earned all of these distinctions and more. He has managed to support himself through print sales for more than 40 years. His online portfolio (ralphgibson.com) is extensive and powerful, filled with wonderful photographs all made exclusively with Leica cameras. As noted by the former director of the Whitney Museum, David Ross, if he hadn’t chosen photography, Gibson probably would have become a graphic designer— his compositions are that elegant and formal. Indeed, many of the high-contrast, surreal images he showed at the PRC were masterful and thought provoking. But just as many of them seemed to have made the cut for no better reason than the name-and- place-dropping opportunities they presented; little more than somewhat interesting snapshots made with those expensive cameras.

Gibson stated that he is only as good as his next print, and that he wants to create not photographs, but “a photography. He didn’t explain what he meant by that. He also said that he’s not interested in how something looks, but rather “how it feels for [him] to be looking at something”. Lofty prose, that, and potentially a rhetorical minefield coming from someone whose most well-known images include that of a cheeky young nubile gently coaxing a feather from between the bared lobes of her derriere. Photographers have been saying such things for as long as I can remember, and only rarely make pictures that say anything at all to anyone other than themselves and the ranks of incestuous art-world sycophants or new age nitwits hardwired to subscribe to such drivel. Or ass men.

Where he lost me, and I suppose what became the catalyst for this essay, came about three-quarters of the way through his presentation. He flashed a familiar picture on the screen, a Catholic priest’s chin and Roman collar severely cropped and contrasty, and called it his “old favorite”. His new favorite, an image shot over the shoulder of a man in silhouette gazing at his lover’s tattooed backside while holding a sketchbook displaying a photograph of a classically sculpted male figure, was as trite as the priest’s shot was remarkable. But it somehow proved, to him at least, that a photographer using a digital camera and Photoshop would never be able to make pictures like his.

It was all I could do to keep from blurting out from my catbird seat second-row center “Now hold on a second, sailor. That is simply a heapin’ helpin’ of BULLSHIT!” It appeared to me that what he was saying was that what he had done with his Leica, some film and a darkroom was better than what I or my students would ever be capable of doing simply by virtue of the different tools we use to do it.

I go to great lengths to instill in my students my belief that, regardless of what technology they choose to employ, photography is still photography, digital or otherwise. If their goal is to make highly complex photographic illustrations using all of Photoshop’s smoke and mirrors, they should knock themselves out learning how to do it to the highest level of quality that they can. If, on the other hand, they want their photographs to be unmanipulated, faithful representations of what they see and feel, they can do that with a digital camera as easily and masterfully as they ever could with a film camera, and probably even more so. Photoshop is a digital darkroom as well as a retoucher’s studio, and as it’s always been, it’s up to the photographer to decide how much of either to employ.

Later, during the question and answer session, I asked him what he would say to a student learning digital photography in 2008, based on what he said about his new favorite picture. He cut me off before I could finish, saying, “I know where you’re going with this. First of all, it’s not digital photography, it’s digital IMAGING…” the same way he might say “it’s not fois gras on that silver plate there, it’s ground-up goose guts.” He continued with his answer, but frankly, I tuned much of the rest of it out as I tried to figure out whether he was arrogant or simply misinformed. I vaguely remember hearing something about f-stops, shutter speeds, and him knowing about all “those cameras” that he would never use unless he was paid enough money to do so. With that one definitive proclamation, he had dissed my question, my students, and the present and future state of his medium.

As he finished his answer and turned abruptly away from me to take another question (cutting off any chance of the follow-up that I was trying to formulate) I heard a piece of music beginning to loop around in my head. It was the work of another American ex-pat now living in Provence, the truly brilliant underground cartoonist-cum-banjoist R.Crumb. Backed by his honky-tonk ensemble The Cheap Suit Serenaders, he recorded what would have made the perfect soundtrack for Mr. Gibson’s attitude toward those of us unfortunate enough to be photographers in the digital age. It’s an incessant little ditty entitled “Fine Artiste’, and a line or two of it goes like this:

Well, my paintings are famous

And they’re worth lots of dough

Pretty girls all hang around my gallery show

I’m as good with my paintbrush as I am with my lips

Stick around honey, learn some aesthetic tips!

Baby I’m a Fine Artiste

Baby I deserve to be kissed...

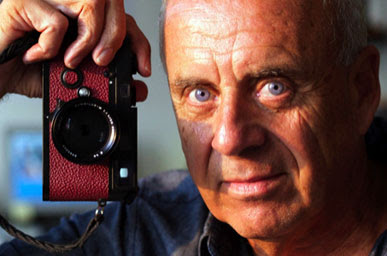

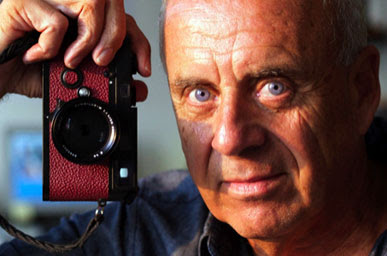

Mr. Gibson, I suspect, will keep on truckin’. There’s now a Ralph Gibson limited edition of 50 specially modified and autographed Leica MP camera bodies available from his online “boutique” all tarted up provocatively in black lacquer and red leather. Owning one of these little trollops will set you back $5000.00 sans lens, which is about 2 grand more than the stock version of the same camera. One would drape perfectly around one’s neck while strolling down the Promenade des Anglais, and would surely be the perfect instrument for creating "a photography" of one's own.